Tama Salim – When I was growing up in the 1990s, history was something to be memorized, not understood.

Like most Indonesian schoolchildren of my generation, I was taught a single, sanitized version of the national past. It came bound in flimsy government-issued textbooks, echoed by our teachers and reinforced by the encyclopedic RPUL (Rangkuman Pengetahuan Umum Lengkap) that glorified an endless roster of national heroes. For a shy, disinterested student, it was a distant, flat reality; full of names, dates and acronyms that bore little connection to my own life.

Without today's online references, search engines or artificial intelligence study buddies, we relied entirely on memory. And memory, unfortunately, was never my strength. I scraped by with mediocre scores, unable to retain what felt like a rigid and impersonal script. There was no incentive to question, let alone internalize, any of the "facts" we were taught. History class wasn't about the moral arc of a nation; it was just another hurdle to graduate.

Ironically, it was my family, not the school system, that taught me to care about the past.

My mother, fiercely proud of our Minangkabau lineage, made sure we knew where we came from. She would often remind my brother and I that we were descended, however distantly, from royal blood. I internalized that mythology perhaps a little too eagerly, secretly walking taller on the playground, certain I carried something noble in my veins. But it also planted a deeper seed: that personal histories matter, and that what came before us shapes who we become.

Then there was my maternal grandfather, my Opa. A veteran of the revolutionary wars and a former journalist who ended up working for the Departemen Penerangan, the New Order's propaganda ministry, he was a man of deep curiosity and quiet conviction. His shelves were lined with Encyclopedia Britannica volumes and worn copies of the World's Greatest Classics. He rarely spoke of the war, but when he did, it was with nuance, humility and the clarity of someone who'd lived what the rest of us only read about.

My Opa taught me that history doesn't belong to any single authority. It is pieced together from lived experience, family lore, conflicting memories and multiple truths. It is something you chase, not something handed down complete. And it was one of the reasons I became a journalist myself.

In hindsight, I realize how rare that gift was. Most of my peers never had access to competing narratives. We accepted what we were taught, never thinking to ask whose version it was. That early conditioning is hard to undo, and many never do.

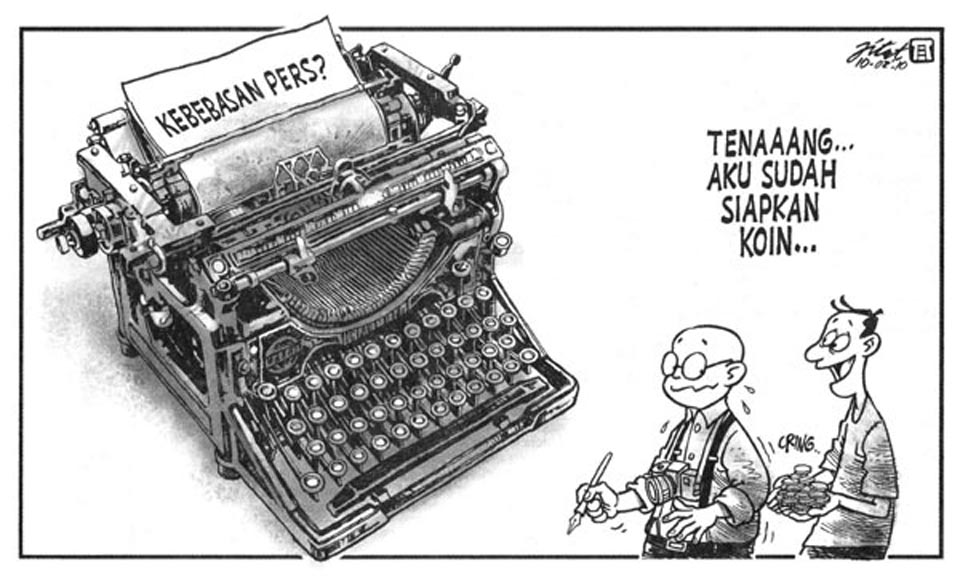

Which is why the government's current push to rewrite our national history books feels so ominous.

The full article can be read at: https://weekender.thejakartapost.com/main-story/2025/08/19/the-battle-over-memory.html