Reza Gunadha – Many academics, intellectuals and Indonesian youth can speak fluently on the historical ideas of ancient Greece and modern Europe.

But when speaking about the history of their own nation, they are unsure and hesitant or just parrot historical texts or mainstream literature and thus fail to understand the history of their own country.

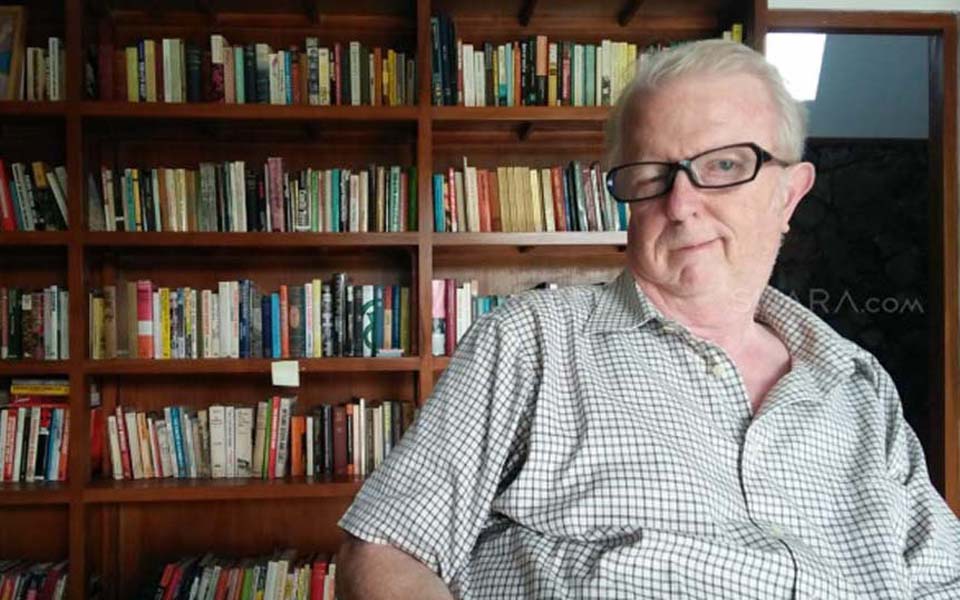

At least that is the criticism put forward by Max Lane, an Indonesianist from Australia and the first person to translate Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Buru Quartet into English.

The Buru Quartet is a popular term for the four novels by Indonesia’s foremost author: This Earth of Mankind (Bumi Manusia), Child of All Nations (Anak Semua Bangsa), Footsteps (Jejak Langkah) and House of Glass (Rumah Kaca).

“The [Indonesian] people struggled and sacrificed making a great effort to achieve independence [from the Dutch]. But what did they want after independence?”, asked Max during a discussion at the launch of his new book Indonesia is not Present on this Earth of Mankind (Indonesia Tidak Hadir di Bumi Indonesia) at the Cipta Gallery III at the Taman Ismail Marzuk Cultural Centre in Cikini, Central Jakarta, on Saturday August 12, 2017.

As an Indonesianist – a foreign academic who has specialises in studying Indonesia – Max’s typology is unique. He doesn’t just conduct research, publish articles and attend one seminar after another, but he is also active in the grass-roots democratic movement in Indonesia. He is an activist himself.

The pages of mainstream Indonesian history books do not record Max’s name as being part of the historical progression of social change from the authoritarian New Order (Orba) regime of former president Suharto. But for the exponents of the mass movements of the 1980s until 1998, Max can be said to be a fellow traveler.

In the 1990s, when the Suharto regime was still firmly in power, Max took part in the publication of the tabloid Green Left Weekly in Australia.

Through this tabloid, Max published critical analysis about the Indonesian government or reportage on human rights violations by the military.

Likewise it was Max who courageously began the project of translating Pram’s works into English so that the international community could have an alternative perspective on Indonesia’s history and likewise the Dutch colonial era which, as it turned out, would be inherited by the administrations in the eras that followed.

Max also expressed the irony that in many other countries, Pram’s works are taught in high-school, yet in Indonesia itself, Pram’s works are not included in the educational curriculum.

According to Max, the government is afraid of the younger generation becoming acquainted with Pram and the works of other great Indonesian authors. This is because if they read such literature, the ordinary people will also learn about the real history of the national struggle for independence.

Suara.com journalists Abdus Soemadh from the Central Java city of Yogyakarta had an opportunity to conduct a special interview with Max Lane last week.

During the interview, Max related the story of his involved journey with all of the problematic issues faced by Indonesia since the 1970s, when he first visited this country.

He also revealed how to really understand Indonesia – through the works of the people silenced by those in power – through Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet.

The full interview follows:

When was the first time you came to Indonesia, and what did you work as?

I came to Indonesia in 1969 as an Indonesian studies student at the University of Sydney. I was in Indonesia for almost a year that time round. I was routinely visiting for one to four months. I moved house a lot, traveling around seeing Indonesia, mostly Bali and Java. I also went to Singapore and Malaysia.

When did you first meet Pramoedya and where?

The first time I met Pram was in 1980 at Utan Kayu in Jakarta. I was introduced to him by a friend who was once Pram’s student when they studied at the Res Publika University (which was destroyed when Suharto began taking over power).

I met him in the 1980s after he had been released from Buru Island [prison camp]. We chatted about many things, too many to remember. He related his many life experiences when he was arrested, sometimes he talked about Indonesian history, Indonesian politics. He related many things.

What in your opinion was Pram like?

Pram was an extraordinary person. He wrote really good books. He talked a lot about his experiences. I think that This Earth of Mankind and the Buru Quartet were best of his works.

There is no rival to Pram’s books about Indonesia’s origins. The essence of his works is the question, “where did Indonesia come from? Following this he begins to write about this. Yes, he wrote all of this on Buru Island. But, he compiled the material for his writings long before this.

How did you come to be the translator of the Buru Quartet, where was it published? And what were the ins-and-outs of the translation?

I met Pram in the 1980s. At the time I was working at the Australian Embassy [in Jakarta]. Bung [brother] Yoesoef Ishak – a former Buru Island political prisoner and founder of Hasta Mitra (the first publisher in Indonesia to publish Pram’s works) – first showed me the text of Pram’s Buru Quartet.

At the time, I read through it very quickly, in one night, because I was infatuated [by the story]. The next day I talked to them about translating the work into English.

Prior to this, I had already translated WS Rendra’s (dramatic) story The Struggle of the Naga Tribe. I told Bung Yoesoef and his friends that I was very enthusiastic about translating Pram’s books.

After I’d translated them, I took them overseas and they were published by Penguin Books (an English publisher founded in 1935) in Australia and the United States.

(Max then shows us the first English edition of This Earth of Mankind published by Penguin Books.)

What were the difficulties you faced in translating Pram’s Buru Quartet?

There were difficulties, namely that Pram said to me that he wanted his works to be able to be read widely, so the language should not be convoluted.

If you want to see the Indonesian-ness and irony of Indonesia, it’s not always easy in Pram’s works. It’s not easy. Because, these Asian literary works, which have stayed in print for more than 35 years, are regarded as being quite amazing, that they are still being read.

During the translation of This Earth of Mankind I was working in Jakarta. The rest were done in Canberra, Australia. I translated the four books over six years more or less.

What did you learn from Pram’s Buru Quartet?

People who seriously want to understand Indonesia, they should read Pram’s books. Many foreign readers say that if you want to understand Indonesia, read Pram’s books. If Indonesian people want to understand Indonesia, they have to read Pram’s works too.

Pram’s Buru Quartet conveys the idea that 70 years before he wrote his books, the Indonesian people did not exist on the face of this earth.

Indonesia only existed on the face of this earth because of its own history, which is recorded in the quartet. Because, Pram wanted everybody to know, that in order for Indonesia to be able to move forward, they must study and familiarise themselves with the history of their own nation in a way that his true and honest.

Essentially, people must understand that it was the ordinary people who created something that did not yet exist. The ordinary people created Indonesia, not the elite class.

Do you think that his works should be read in sequence?

It’s best if they’re read in sequence, because that is to read the character’s story (Minke – Raden Tirto Adhisoerjo) from when he was young until his death. It’s very important to read it in order. In the fourth chapter (House of Glass) it contains parts which related back to the first chapter (This Earth of Mankind). People won’t be able to understand This Earth of Mankind if they don’t read all of his works in sequence.

Indeed This Earth of Mankind tells the story in Minke’s voice, but which of Minke’s voices? That is the question. People will only know the answer to this question if they read chapters three and four, especially chapter four. So, it’s important to read them in sequence.

What do you know about Pram at the time he was drafting the Buru Quartet texts?

Pram related how before the 1965 affair, he had already complied a lot of materials, pre-Indonesia historical stories.

For example, he sought out and collected copies of the newspaper Medan Prijaji (the first newspaper managed by the Indonesian nation, namely Tirto Adhisoerjo). Other writings of the same period. He studied and conducted research. Pram’s writings in many newspapers in the 1960s were actually a result of his research on Indonesia’s national history.

Were there any consequences for you as a non-Indonesian national who was close to Pram and translated his works when the Orba was still firmly in power?

There were some consequences. There was a squabble with the Australian Embassy because it was deemed inappropriate, not okay.

They said it isn’t fitting for an Embassy staff member to translate banned books. If you want to do that then don’t work [for us] in Indonesia, that was the message from the Australian ambassador at the time.

After several months of not really fitting in at the Australian Foreign Affairs Department I left. After that I concentrated fully on translating Pram’s works, until all my savings were gone. I found another job in Australia to pay for all the expenses.

What do you know about the Buru Quartet’s position among groups in the movement to overthrow Suharto?

Many facts. The books were published in Indonesia [starting] in 1981. So from 1965 to 1981, everyone who Suharto disposed of on Buru Island was deemed by the public as being ruthless criminals. From members of the PKI [Indonesian Communist Party], leftist groups, Sukarnoists [followers of Indonesia’s founding president Sukarno], all were branded evil. That was the propaganda of the Orba.

But, after the Buru Quartet was published, Indonesia’s youth, particularly students in the Orba era became more aware. It turned out [despite being banned] that the books were really good, democratic, filled with humanitarian messages, and most importantly the perception that the books were not the works of an evil person.

Moreover, groups at the time who had previously hated Pram said, “Perhaps those jailed on Buru Island are not evil people. This is a great book, perhaps those arrested were not evil, it’s the Orba propaganda that’s evil”, and so forth.

Through Pram’s Buru Quartet, students then began to explore Indonesia. They began to read left leaning books, such as the books of President Sukarno, and Pram.

It has to be acknowledged, that the essence of the Buru Quartet is resistance. Nyai Ontosoroh resisted. Minke resisted. Darsam resisted. It was only Annelies who didn’t resist, and she was banished overseas then killed.

So these books teach the spirit of resisting injustice, feudalism, racism. Pram’s books had a huge impact on those who read them.

In the books it also articulates the importance of writing. So, in the 1980s and 1990s, many activists began to understand about developing literacy and an organisation. The books also became a guide on how to fool intel [intelligence officers] and the police.

Because of this, the books became a source of spirit to resist, and at the same time became a guide on the need to work to build an organisation and publish a newspaper, how to confront the power of the police and intel.

In Chapter 4, House of Glass, it teaches how intel and the police hunt down and kill Minke. It’s important for activists and Non-Government Organisations to read this.

Did you know that This Earth of Mankind is be made into a film by [prominent Indonesian filmmaker] Hanung Bramantyo? Do you agree with him making it into a film?

It should have been made in to a film a long time ago, but there was no one who was up to it, there is already a version of the film overseas. It is indeed time, it should have been done long ago. Yes during the Orba period it was impossible. Hopefully it won’t be censored.

If you want to make the film about Minke, then try focusing on Nyai Ontosoroh’s story, that would be an approach that could be adapted. The other approach would be to put the main focus on Minke. He did indeed face big challenges, because in picturing Minke, on the one hand he was still studying at high school, still young, his life experience was minimal. But on the other hand, he was part of the elite which was not acquainted with the ordinary people, then after This Earth of Mankind he becomes acquainted with his own society.

His life experiences attending school at the HBS (Hogere Burger School – the equivalent of high school during the Dutch colonial period) were beyond the experiences of a pribumi [a native]. First because people studying at the HBS were already privileged. It was difficult for a Javanese to get into the HBS. On the other hand his life [experiences] were minimal, but on the other hand his life was special.

In the following book (Child of All Nations), Pram writes about Minke’s course in life to become the first Indonesian, the first Indonesian human. He is no longer Javanese, no longer Dutch, he moved on to become Indonesian, although he is not conscious of this.

Minke, in This Earth of Mankind, has yet to encounter the word “Indonesia”. But he is a person full of experiences, he already has the seed to grow towards becoming a pioneer. That is the big challenge for a film of This Earth of Mankind. Hopefully then can be able to adapt the story.

What do you hope will be contained in a film of This Earth of Mankind?

The book has so many things in it, so many messages, so much that is depicted. I hope that the message of resistance against injustice can be accentuated.

Second, something which is much deeper, is the film could record the process of how a person matures because of their experiences, developing towards a person of potential, not just becoming an Indonesian, but at the same time becoming a pioneer of a national awakening.

What needs to be depicted is not that Minke has becomes the founder of the newspaper Medan Prijaji, but his journey towards this, his experiences.

Would it be appropriate for Pam and his works to be included in the language, Indonesian literature or national history educational curriculum?

It should already be included. Not just Pram, but many others. To this day, Pram’s books have yet to be introduced to Indonesia’s younger generation, yet it is already 35 years since Suharto was overthrown.

My hope is that the Indonesian government will revise the education curriculum, so that it’s like other countries. In addition to this, the important Indonesian literary works need to become required reading, for primary and high school students, without censorship.

Why so? Because I think that studying the literature of a nation is to understand the journey of that nation’s [birth]. By reading novels, short stories, poems, they can understand the process of how their nation was established.

In Australia, when I was in primary school we read novels, then we wrote critiques. In America, Singapore, Malaysia it’s the same. Only in Indonesia do students not read literature.

The authorities do not want the ordinary people to read literature. Why don’t the authorities want to see the ordinary people reading Pram’s works and literature in general? This is the big question that needs to be answered.

Overseas, the works of important authors have to be read by students at primary and high school level. Many are given Pram’s books to read.

If you visit the Amazon.com website you’ll find books published for teachers so they can teach This Earth of Mankind to primary and high school equivalency students.

From Australia to the United State and the Philippines, Pramoedya’s books are taught to students in schools. Only one great county does not teach Pram’s works to its younger generation of students: Indonesia.

[Translated by James Balowski. The original title of the article was Max Lane: Kenapa Indonesia Takut Ajarkan Pramoedya di Sekolah?.]